to grant to those who mourn in Zion—

Isaiah 61:3

to give them a beautiful headdress instead of ashes,

the oil of gladness instead of mourning,

the garment of praise instead of a faint spirit;

that they may be called oaks of righteousness,

the planting of the LORD, that he may be glorified.

Author: Burrows

-

A Diamond in the Rough

-

There is No Such Thing as Normal

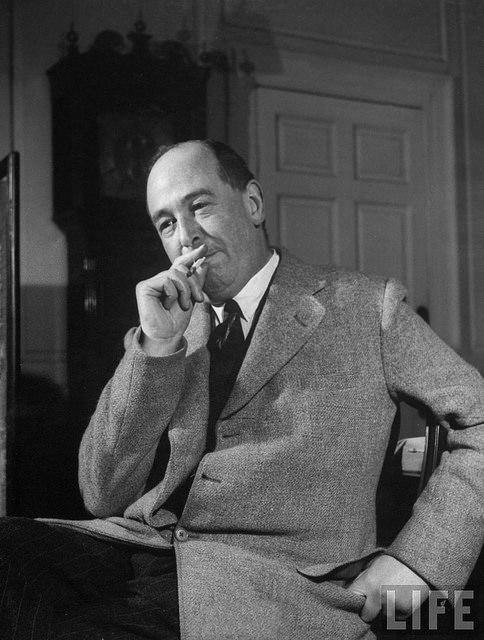

The war creates no absolutely new situation; it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it. Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself.

If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun. We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal.

C.S. Lewis, “Learning in War-Time”, from The Weight of Glory, p. 49 -

How to Become a Theologian

For as soon as God’s word takes root and grows in you, the devil will harry you, and will make a real doctor of you, and by his assaults will teach you to seek and love God’s word. I myself (if you will permit me, mere mouse-dirt, to be mingled with pepper) am deeply indebted to my papists that through the devil’s raging they have been, oppressed, and distressed me so much.

That is to say, they have made a fairly good theologian of me, which I would not have become otherwise.

Martin Luther, quoted in The Trials of Theology, p. 29 -

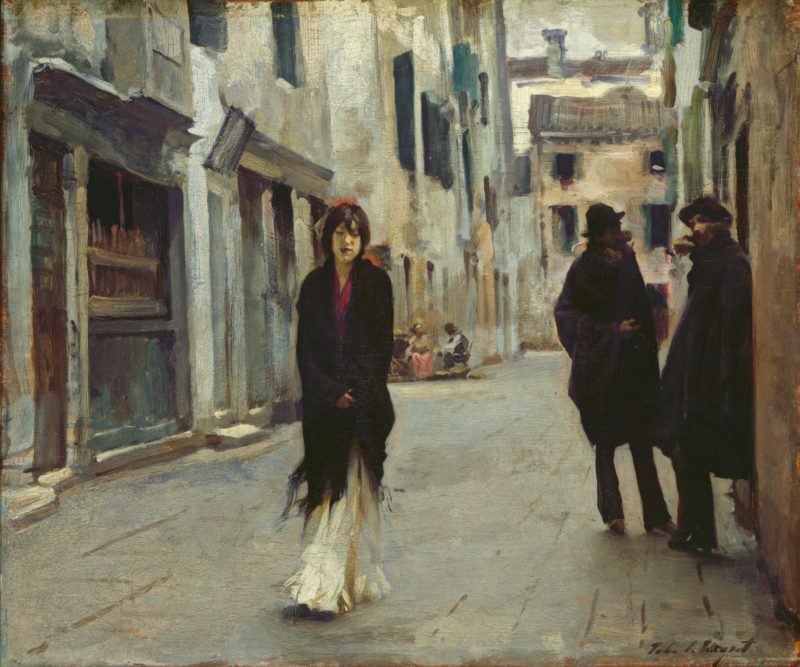

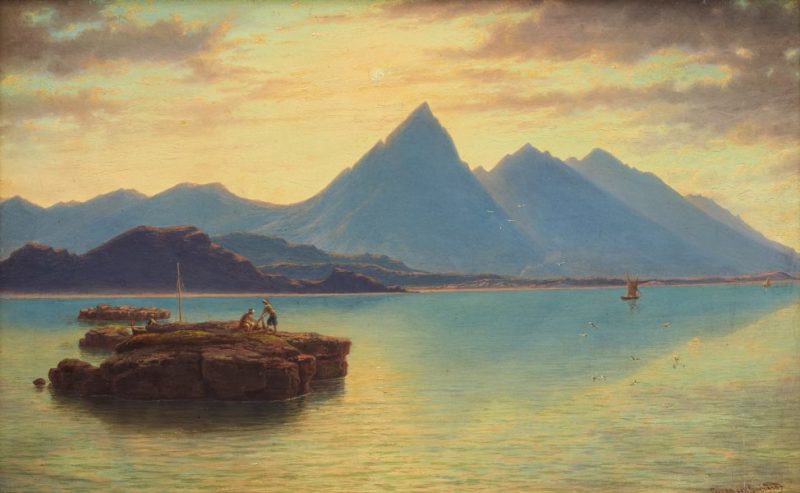

They Were Fishermen

Passing alongside the Sea of Galilee, he saw Simon and Andrew the brother of Simon casting a net into the sea, for they were fishermen. And Jesus said to them, “Follow me, and I will make you become fishers of men.” And immediately they left their nets and followed him.

Mark 1:16–18 -

On Personhood and Love

Professor Haldane himself illustrates the present state of mind very well. He thinks that if one were inventing a language for ‘sinless beings who loved their neighbors as themselves’ it would be appropriate to have no words for ‘my’, ‘I’, and ‘other personal pronouns and inflexions’. In other words he sees no difference between two opposite solutions of the problem of selfishness: between love (which is a relation between persons) and the abolition of persons. Nothing but a Thou can be loved and a Thou can exist only for an I.

A society in which no one was conscious of himself as a person over against other persons, where non could say ‘I love you’, would, indeed, be free from selfishness, but not through love. It would be ‘unselfish’ as a bucket of water is unselfish.

C.S. Lewis, Other Worlds (1975), 83–84. -

Solemn Pleasure of the Imagination

I am not sure that anyone has satisfactorily explained the keen, lasting, and solemn pleasure which such stories can give. Jung, who went furthest, seems to me to produce as his explanation one more myth which affects us in the same way as the rest. Surely the analysis of water should not itself be wet?

I shall not attempt to do what Jung failed to do. But I would like to draw attention to a neglected fact: the astonishing intensity of the dislike which some readers feel for the mythopoeic. I first found it out by accident.

A lady (and, what makes the story more piquant, she herself a Jungian psychologist by profession) had been talking about a dreariness which seemed to be creeping over her life, the drying up in her of the power to feel pleasure, the aridity of her mental landscape. Drawing a bow at a venture, I asked, ‘Have you any taste for fantasies and fairy tales?’ I shall never forget how her muscles tightened, her hands clenched themselves, her eyes started as if with horror, and her voice changed, as she hissed out, ‘I loathe them.’

Clearly we here have to do not with a critical opinion but with something like a phobia. And I have seen traces of it elsewhere, though never quite so violent. On the other side, I know from my own experience, that those who like the mythopoeic like it with almost equal intensity. The two phenomena, taken together, should at least dispose of the theory that it is something trivial. It would seem from the reactions it produces, that the mythopoeic is rather, for good or ill, a mode of imagination which does something to us at a deep level.

C.S. Lewis, Other Worlds (1975), 71–72.